Architecture, eroticism and art as therapy

After 28 years working in universities, artist Sandra Kaji-O’Grady recently finished designing and building her dream home with her partner John in Upper Coopers Creek. Replacing bustling campuses with the rustling forest has helped Sandra spend more time than ever on her art and right now, that means creating collages.

Words and photos by Andy Summons.

In stark contrast to the dusty road in, Sandra’s property is an oasis of vibrant green backed by the comforting white noise of a creek and waterfall at the base of their property.

I asked Sandra what drew her to collage and she started pointing around her living room. “I made that sculpture, those two paintings and this sculpture here too,” she smiles. “The collages are a more recent project after a lot of others across different mediums. I’ve always made stuff and I work in series – there are heaps of those car accident paintings and I worked on these straw sculptures for two years. I’ll become consumed by something, dive down into it until I exhaust it and then pick up another trail. My practice is wildly discontinuous and explorative and erratic.”

Sandra was an architectural educator and academic until recently. She was the head of the Architecture school at the University of Technology Sydney and the Dean of Architecture at University of Queensland. She spent 28 years in universities and explored her art practice the entire time.

“I grew up in a lower-middle class family in the suburbs of Perth. I went to a selective art high school, which opened up the possibility of art as a career. Those who went to that school and became full-time artists tended to be realist painters, like Tom Alberts. It was a bit of a traditional skills-focused education; we learnt to paint through endless still lifes and life drawing. I’ve spent a lot of time trying to break away from that training.”

Despite her fervour for the arts, other interests intervened. She worked out the quickest way to get away from Perth was to apply for a Rotary Exchange student scholarship, which landed her in Canada for a year.

“I got into medicine and deferred – fortunately I was saved from that path by my exchange host parents. They told me I’d be a horrible doctor because I lacked empathy.”

Sandra heeded her exchange parents’ advice and enrolled in a Bachelor of Arts. A friend of hers who did an exchange in India was studying architecture and told her to come and check out the studios. When she walked in, she knew she had to switch degrees.

“I couldn’t believe how much fun everyone was having but I had no idea what it would be like to be an architect. Studying architecture was fantastic. I still love the process of form making, thinking through space and the problem solving aspect, but the working reality was very different. The West Australian Government Works Department where I had my first job as a graduate was sexist, bureaucratic and miserable.”

After persevering for a few years, and completing a degree in Women’s Studies at Murdoch University in the evenings, she applied to to do a PhD with feminist philosopher Elisabeth Grosz at Monash University. Her doctorate was on Serial Music and Art and led to some valuable creative inspiration for her art practice. She was intrigued by artists and composers using self-imposed constraints.

“Serial art is setting up a set of predetermined rules and procedures without knowing what the outcome is going to be. It’s the opposite of the way I worked so it fascinated me as a process. To abandon representation and the idea of art as personal emotional expression and instead work with givens within a strict framework still intrigues me.”

Sandra began looking at the connection between the Serial Musicians in the 1920s and Serial Artists in the 1960s, like Sol LeWitt, and the way in which architects worked with constraints in the pre-digital age.

“There was also a group of French writers called the Ouilipo who competed with each other to devise the most difficult rules. Georges Perec, who wrote a novel in French without the letter ‘e’ was decidedly the winner. By comparison, my rule, to make art using only materials from the office stationery cupboard was pretty tame. For each of the straw sculptures I had to use up every single piece in a packet – no more, no less – but again, that’s very loose compared to the serial artists. Even now I love making with given materials and augmenting them. I find that much more productive than working with a blank canvas.”

Sandra’s art practice became therapy, what she called her antidote to work as an academic. She started creating collages in her last two years as an academic manager.

“I was an academic manager for fifteen years but I wasn’t really brilliant at managing people, I found it really difficult. In those last couple of years, I was pretty disenfranchised – not that anyone could tell – I was still publishing books and doing everything demanded of me.”

The collages are the result of work frustrations, building her home in Upper Coopers Creek and a string of summer storms.

“I bought a fashion magazine for my daughter for Christmas and she left it behind. We were living in an old banana shed while we built our house. It was one of those very wet Januarys and I had no other art materials so I started cutting up the magazine and sorting the pieces into different categories: fabric in different colours, clouds and people. It gave me pieces to use and from there I just couldn’t stop making collages.”

“I’ll become consumed by something, dive down into it until I exhaust it, and then pick up another trail. My practice is wildly discontinuous and explorative and erratic.”

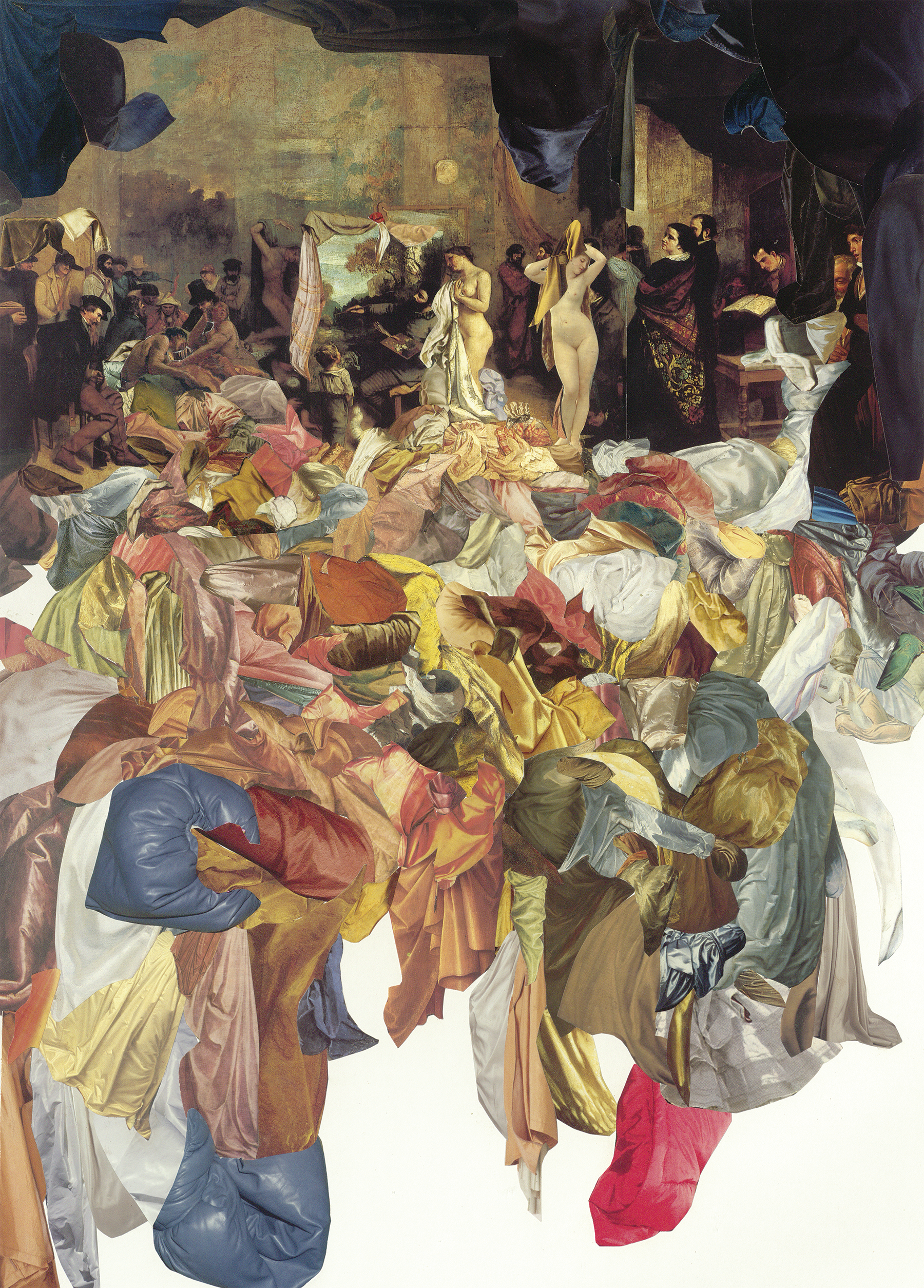

I ask Sandra about the connection between years of academic teaching, writing and feminist studies, architecture and the aspects of the serial art movement she retains in her work. She pauses and says, ‘I think I’m the connection, I’m not sure there’s much more to it than that,’ and laughs. Sandra is exacting with her work and deliberate about the themes in each series. She takes historical imagery, pieces it out into different subject matters and then exaggerates certain elements to subvert the original intention of the artwork.

“I’m interested in the politics of imagery and a lot of my collages set out to subvert intention by abstracting certain components, often with humour. There are a lot of religious undertones – especially in the works using historic images. I’m especially interested in the female nude and finding ways to expose the narrative painters used to justify naked women in their paintings. I do that largely through excess and humour. Humour is a way to make profound observations in a way that isn’t dry, heavy or journalistic. I sometimes start with a famous and much-reproduced image (like Manet’s Olympia), take an element from it, and exaggerate it and fetishise it.”

She shows me a collage where a servant is proffering flowers from an admirer to a prone woman, who has been overwhelmed by a crowd of hands and flowers cut from bridal magazines (see p.6).

“I was into the idea of the flowers being thrust as an offering in quite a phallic way and how that flower motif – the hint of the ‘deflowering’ to come later – is a feature of the wedding ritual.”

Sandra created a stunning series from a tourist brochure of the Sistine Chapel, which brilliantly unpacks the famous artwork with surprising outcomes.

“This triptych (pictured above) takes the three components of the Sistine Chapel ceiling – the architecture, the fabric and the skin and leaves nothing out. Every component of the ceiling is in these three collages. When you think about the Sistine chapel, focus is drawn to the gestures and the people but I was intrigued by the proportion of the architecture and the drapery with its vulvic eroticism. All those folds! I love how throughout that period of painting, all the biblical scenes were excuses to render a kind of pornography – not morally but functionally.”

Sandra is deeply enjoying reconnecting with collage after some time away from it while finishing the house and making all its furnishings with her housemates. We stand around her dining room table, the smell of sticky chai lingering in the crisp forest air, as she flips through huge folios of collages that she hasn’t shown many people. She draws my attention to certain features – famous artworks, peculiar books she used as source material, and laughs out loud as she points out the subversive humour. “They have serious themes, but I think they’re hysterical too.”